April 30, 2015

Topic

“A ‘data-driven’ approach can begin to demystify all the anecdotal debate around the polarizing topic of ‘gentrification.’”

Rick Cole

Deputy Mayor for Budget and Innovation

City of Los Angeles

This is the second of two articles on equity in planning. The first examined equity planning strategies and tools.

California is poised to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in revitalizing communities through implementation of SB 375-required Sustainable Community Strategies and cap-and-trade funding allocations.

In a state already grappling with wide disparities in educational achievement, air quality, income levels, healthy food access, transportation and housing, it’s essential that – as we prepare for major new investments – we consider new tools and models for closing the equity gap.

SB 535 assures that a significant portion of cap-and-trade funds go either directly into disadvantaged communities or to “benefit” disadvantaged communities. The Affordable Housing Sustainable Communities Program provides new, albeit limited dollars to fund affordable housing in infill and transit-oriented developments. This is a good step in the right direction but we need much more consideration about the overall impact of these new investments on equity in addition to the larger influence of local spending.

One key concern at the nexus of sustainability planning and equity – an economic Catch-22 for many communities – is how existing residents are often pushed out when the neighborhood is revitalized, or “gentrified.”

Taking the mystery out of the revitalization-displacement ‘conflict’

“A ‘data-driven’ approach can begin to demystify all the anecdotal debate around the polarizing topic of ‘gentrification’,” Rick Cole urged in The Planning Report earlier this year (“LA Mayor’s I-Team Seeks to Minimize Displacement during Urban Revitalization“).

“If a neighborhood suddenly becomes more attractive in the marketplace, it does seem logical that residential and commercial rents will increase. What’s missing from that equation, however, are two other factors,” said the Los Angeles deputy mayor for budget and innovation and former Pasadena mayor – and a speaker at the Yosemite Policymakers Conference conference last month. “First, what if revitalization was so widespread across Los Angeles that attractive neighborhoods were not a scarce commodity? In other words, what if the supply of attractive areas was increased to meet the demand? Second, what if rising wages and business activity allowed existing residents and local businesses to prosper in an improving neighborhood? Targeting both these missing factors could significantly reduce displacement.”

Los Angeles was one of a dozen cities to receive a $2.55 million Bloomberg Philanthropies grant to create “innovation delivery teams” aimed at solving intractable problems – Los Angeles picked the gentrification-displacement challenge as its target – by applying a structured, data-driven approach to take “best in class ideas” and deploy them to deliver results.

LA’s i-team helps coordinate a number of placemaking efforts (including its Great Streets initiative and the federal Promise Zone designation) with broader anti-poverty strategies such as efforts to raise the minimum wage and improve the effectiveness of the City’s FamilySource and WorkSource programs – which help strengthen the economic security, income potential and consumer spending of individuals and families in the neighborhoods.

“We need to look at a wide range of alternative approaches to the opportunity of bringing new life to older neighborhoods. I’m particularly interested in looking at placemaking that builds on local character and culture as well as microcredit lending and other initiatives that promote entrepreneurship in the inner city,” Cole concluded in recommending promising affordable-housing initiatives in New York City and Boston.

How to get both

In “It’s Not Either/Or: Neighborhood Improvement Can Prevent Gentrification,” Rick Jacobus delves deeper into the economic logic that can get us out of this seemingly intractable situation.

“The paralyzing thinking goes like this: We want to improve lower-income neighborhoods to make them better places for the people who live there now but anything we do to make them better places will inevitably make people with more money want to live there and this will inevitably drive up rents and prices and displace the current residents, harming the people we set out to help (or, in many cases, harming the very people responsible for making the neighborhood better through years of hard work) and rewarding people who drop in at the last minute to displace them,” Jacobus said.

He goes on to explain that while residents in low-income communities want their neighborhoods to be cleaner and safer and have a few more stores, they generally don’t want their neighborhoods to become “fancy,” “flashy,” “hip” or “trendy.”

For a lower-income community, modest “improvements” that make the place more attractive gradually to slightly higher-income households may actually provide the most promising defense against gentrification.

Slow play: How to evolve the new without displacing the old

“The people who will choose to move in will be more likely to be people who are comfortable with the existing character of the neighborhood. This kind of gradual, sustained, and smaller-scale improvement leads to a broader but still contiguous income mix,” Jacobus explained. “A gradual influx of moderate-income homebuyers [rather than a mix of high and low end with no middle] creates displacement at a scale that is closer to the scale of our affordable housing resources, while flipping a neighborhood to high-end housing displaces people faster and makes the gap between market prices and what is affordable so great that it is simply ridiculous to discuss “affordable housing” as an appropriate response.”

Strategies such as encouraging homebuyers to invest in lower-income neighborhoods along with incremental and sustained investment in commercial revitalization may provide a more sustainable evolution – not dramatically changing the social character of a neighborhood overnight. Alan Mallach outlines additional investment strategies in “Managing Neighborhood Change: A Framework for Sustainable and Equitable Revitalization.”

To prevent the rapid escalation of real-estate values and the displacement that comes with a sudden influx of investment in historically disinvested neighborhoods, cities should move toward a balanced development approach that involves ongoing investment in, and maintenance of, the housing stock, community resources and infrastructure in all neighborhoods, particularly low- and moderate-income neighborhoods with a history of disinvestment.

Cities should also support home ownership and other forms of asset building for existing low- and moderate-income residents to increase stability and resilience against the forces of neighborhood change according to a ‘Causa Justa: Just Cause’ report on “Development without Displacement: Resisting Gentrification in the Bay Area.”

Download the ‘Development without Displacement’ report here.

Incremental community changes

Outside of large public or private investments that may have the unintended impact of displacing existing residents, local governments can pursue a number of “lower hanging fruit” initiatives in partnership with threatened neighborhoods.

They can increase neighborhood stability by addressing property disinvestment:

- Home-repair assistance programs

- Financial-assistance programs for landlords

- Incentives for homeowners

- Community-building strategies

- Neighborhood clean-up efforts

- Targeted code-enforcement programs

They can strengthen neighborhood amenities:

- Appearance of vacant lots and vacant buildings

- Quality of streetscape

- Appearance of commercial areas (facades, parking areas, sidewalks)

- Programming and activity level in open space

- Safety of open space

- Transportation improvements (including frequency and quality of service)

- Access to dining and entertainment opportunities

Strategies that stabilize neighborhoods and build amenity value must emerge from the particular conditions and opportunities, physical and locational assets that the neighborhood offers.

Case Study: Portland

An incremental approach for community-driven, neighborhood economic growth

The City of Portland has developed a five-year plan for incremental neighborhood economic development for lifting up priority neighborhoods, including areas with lagging commercial investment and increased poverty, gentrification pressures, substantial changes due to major public infrastructure improvements, or small businesses losing ground to suburban or big-box competitors.

The plan calls for increasing the profitability of businesses in priority neighborhoods by 4%, real median family income for communities of color by 3%, and net job growth in priority neighborhoods by 1% annually.

It outlines a range of strategies to drive neighborhood business growth and align resources to support neighborhood economic development. In line with the small-scale investment approach, some of the strategies to seed investments in neighborhood economic development might:

- Provide small-scale seed grants to fund neighborhood economic development projects identified and developed by communities within priority neighborhoods and/or culturally specific organizations. Grants of up to $10,000 will support collaborative Neighborhood Economic Development projects, programs and tailored trainings in four to eight neighborhoods per year.

- Expand the Storefront Program to Main Street districts and other priority neighborhoods to provide capital resources for small-scale revitalization projects as part of neighborhood economic development plans.

- Establish neighborhood opportunity districts – small scale, long-term, debt-free urban renewal areas – in three to six commercial hubs within priority neighborhoods to provide resources for area businesses and related improvements for five to seven years. Target annual increment generation will be $20,000 per district the first year and up to $75,000 per district annually by the third through seventh years.

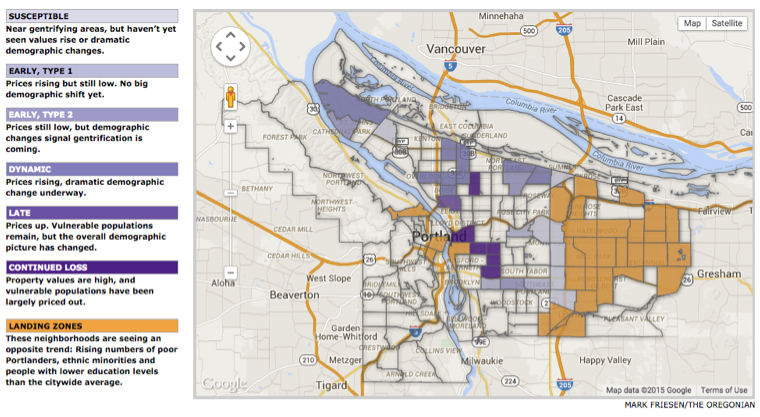

Portland maps neighborhood displacement at risk from gentrification

How can local governments be more proactive to prevent gentrification? One answer is tracking public investments and shifts in housing markets.

The “Development without Displacement” report points out that tracking investment at the neighborhood level can help reveal patterns of uneven investment that can lead to gentrification and displacement, while supporting equitable shifts in investment priorities. Cities can adopt policies that require all their departments to track budgeting decisions by neighborhood, including provision of services, infrastructure and public subsidies for private development (such as the City of Portland’s Budget Maps featured in the last newsletter).

The report recommends that tracking include capital, operating expenditures and maintenance budgets. In neighborhoods with currently or historically low investment, cities should consider small-scale, regular investments in infrastructure, services, and housing and commercial development rather than large, “catalytic” development projects.

The City of Portland is also working to identify neighborhoods on the verge of, or in the process of, gentrifying. As Mallach stressed in “Managing Neighborhood Change,” “Understanding a neighborhood’s existing housing-market conditions merely provides a snapshot of a moment in time – it can only tell a city planner where to begin. Neighborhoods are constantly changing, not only in their real estate market but in other ways that influence housing demand, such as crime, neighborhood schools, or small business activity. Thus, stakeholders need to be able to track how the neighborhood is changing, so that they can see what strategies are working, and when to phase them out in favor of new ones.”

The City of Portland created a computer modeling and demographic analysis to help local government pinpoint spots that might need extra attention to preserve economic and cultural diversity.

Equitable livability: Getting where we want to go

Ultimately, the challenge of creating equitable livability in our communities is an economic development, jobs-housing balance challenge as much as it is strictly a problem of affordable housing and displacement.

We can’t solve this crisis on a parcel-by-parcel approach. We have to consider the citywide context for expanding access to economic opportunities, and reducing social and fiscal disparities. And cities need policies and a realistic game plan to foster development that meets the housing needs of the entire community – not just those of the very poor or the very rich.

Resilient, equitable communities require a truly holistic commitment by local governments. Faced with intricate growth challenges, cities like Portland are institutionalizing their commitment to affordable, livable communities by connecting all City budget priorities and decision-making back to core objectives that emphasize education and youth, economic prosperity and affordability, and healthy, connected neighborhoods.

Technology can provide a pragmatic toolbox, and is making it more feasible for cities, as part of a deeper trend toward data-driven decision-making, to implement community-based, data-driven measures to help prevent the displacement of lower-income residents amid gentrification pressures from an escalating demand for housing. It gives cities the ability to target investments to improve equity based on need by neighborhood – determined through data versus a complaint-based or “peanut butter” approach that just spreads investments thinly across the community.

Most communities can find measures big and small that in the nearer term will spark improved quality of life, economic development and private investment in neighborhoods.