July 30, 2015

Topic

An acre saved is a gallon earned.

– Adaptation of an old proverb

The hidden groundwater supply under our feet is extraordinarily vital to California’s economy and our quality of life. It’s become the “savings account” that we’ve been drawing on to get us through the past four years of drought.

Under normal circumstances, about 35% of California’s water comes from groundwater sources; today this has increased to 64%. Sadly, the consequence is that many of our groundwater reserves are being quickly depleted.

At the same time, many local officials have been, and continue to be, unaware that the land-use decisions they make have been contributing to the “overdraft” problem, making the situation even more serious than it needs to be. It is time to take a hard look at the relationship between groundwater supplies and development strategies.

Understanding the Language of Groundwater

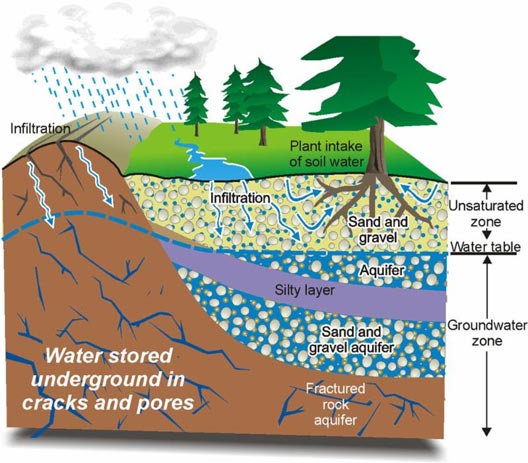

Groundwater is defined as water located beneath the surface in soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. It can be found in many locations.

The largest quantities of groundwater are located in aquifers – basins deep in the ground that are lined with rock or sediment. Aquifers come in different sizes; some of the largest provide water to populations covering several cities and counties.

The largest quantities of groundwater are located in aquifers – basins deep in the ground that are lined with rock or sediment. Aquifers come in different sizes; some of the largest provide water to populations covering several cities and counties.

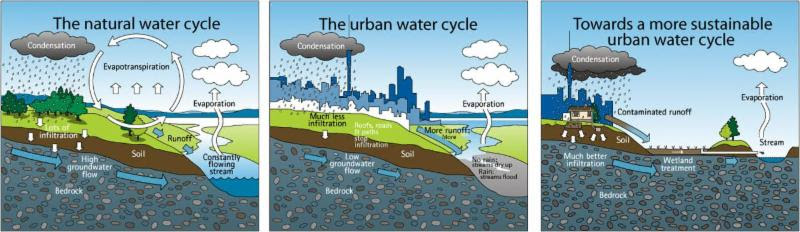

Aquifers are naturally filled when rainwater and urban runoff are absorbed into the soil. Some soils are extremely porous, allowing water to more easily permeate through to the groundwater aquifer. Groundwater recharge areas can be located in or near river/stream bottoms, but can also be found in locations not near streams. These exceptional groundwater recharge areas should be identified and retained, as they play a critical role in our quest to maintain a balance between “deposits” and “withdrawals” from our important underground water savings accounts.

Watersheds are also important in the recharge of aquifers. Watersheds – or basins – are characterized by an entire area from which rainwater (or snow) is collected. A watershed is comprised of up-stream lands that collect snowmelt runoff and rainwater from meadows, creeks, and rivers, and then convey this water to lower elevations where it collects into larger water bodies, is harnessed by man-made “grey” infrastructure, or is absorbed into the ground.

How Development Impacts Groundwater Supplies

According to the U.S. EPA, a relatively undisturbed working landscape can capture 50% of the water that falls on the ground, with half of it percolating all the way down to deep-water aquifers – larger aquifers far underground – with the greatest storage capacity. The remainder collects in shallow soils, or evaporates.

The rate of capture is reduced with every increase in impervious cover: the more roads, parking lots and other structures covering the land, the less water seeps into the ground.

When the amount of cover exceeds 10% of the land area, the ability of nature to replenish groundwater supplies is compromised. This fact has been long-since documented.

In 2002, American Rivers, the National Resources Defense Council and Smart Growth America released the “Paving Our Way to Water Shortages: How Sprawl Aggravates Drought” Report. Their comprehensive study calculated the total gallons of groundwater the nation is losing through sprawl development. The team identified the acres of potential recharge areas covered over in 20 cities between 1982 and 1997, and then modeled the gallons of annual groundwater that each city has lost to urban development.

The results ranged from an average annual infiltration loss of about 10 billion gallons a year in Dallas, Texas (for roughly 300,000 acres developed) to 100 billion gallons a year in Atlanta, Georgia (for about 600,000 acres developed). That amounts to the water used by over 2 million people each year!

A more recent study in 2014 by Texas A&M University documented the rapid development occurring throughout Texas. Open lands are being replaced with roads, parking lots, subdivisions, malls and the like. Researchers found that sprawl development resulted in a loss of 1.1 million acres of open space between 1997 and 2012, covering many potential recharge areas described as “vital to the State’s water supply.”

The Economics of Protecting Groundwater

Back in 1962, researchers from the Texas Board of Water Engineers and the U.S. Geological Survey studied the economics of removing two large structures designed to retain floodwaters, which happened to be located near a prime groundwater recharge area. Removing the structures would enable the capture of 20% more runoff. The team evaluated the cost-effectiveness of this action by calculating the dollar value of using the captured runoff as groundwater recharge. It added up to $7,500 (in 1962 dollars) every year for 50 years – equivalent to nearly $3 million today! It is instructive to consider the amount of money that the loss of inexpensive, naturally replenished groundwater is costing us now.

One thing is certain: As water becomes increasingly scarce, the price to the consumer is steadily increasing. In California, San Francisco and Fresno have already announced that they will be doubling their rates over the next three to five years. And just in the past few months, the cost of water to farmers in Orange Cove has risen from $90 to $1,500 per acre-foot! Increased irrigation costs have an inequitable impact on agricultural communities and those who rely on farm jobs. (Center for Watershed Sciences, UC Davis report on irrigation costs for food)

Early Advice from DWR

The 2009 California Water Plan (updated every 5 years by the Department of Water Resources) recommended that city and county General Plan processes include a discussion of the cost and value of protecting recharge areas, versus the cost of non-protection.

The plan also included additional forward-thinking measures:

- Develop a program to identify actual and potential recharge areas throughout the state and provide that information to Tribal, city and county governments.

- Amend State law to prohibit local decision-makers from developing land for other purposes until it is known if that land is needed for recharge as a part of the local agency’s groundwater management plan.

- Engage the public in an active dialogue using a value-based decision-making model in planning land-use decision that involve recharge areas.

- Establish a “water” element in the General Plan process that specifically requires local governments to consider the cost and values of protecting recharge areas versus the cost of non-protection. Eminent domain should not be allowed to convert potential recharge areas to other uses.

- Require local governments to provide protection of recharge areas for aquifers that have been identified as “sole source aquifers.”

Early Innovators in Groundwater Management

Historically, there has been little, if any, coordination between the water agencies responsible for delivering our water and the local governments that guide and control land use decisions. This is slowly changing, and a few successful efforts can serve as models for others.

New York: The New York City Metro region is well known for protecting its watershed via an agreement between 70 towns, eight counties, private landowners and the U.S. EPA. The city-funded, long-term agreement follows a multi-faceted approach to land conservation, which included the purchase of 80,000 acres of working lands in the Catskills watershed to protect the city of New York’s water supply. The $1.4 billion project allowed the city to avoid the construction of filtration facilities-estimated to cost $6-8 billion-simply by allowing natural processes to cleanse the water.

Austin, Texas: In 1980, the City of Austin adopted measures to protect recharge zones under their jurisdiction. Separate zoning ordinances protect each of its eight individual recharge areas. The policies address impervious cover, density, transfer of impervious cover or development rights, stormwater treatment and detention requirements, construction-site management, and stream setbacks or buffer zones.

Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority (SAWPA): This joint-powers authority in Southern California includes five major water resources agencies, three counties, and several cities located within the same watershed and along the same aquifer, spread geographically from Orange County to the Inland Empire. SAWPA undertakes collaborative planning and implementation activities with multiple agencies and organizations throughout the region. One of these joint efforts brings together city/county planners and watershed stakeholders, an important first step toward developing a system-wide, integrated approach to ensuring that our remaining groundwater recharge areas are not paved over.

Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority (SAWPA): This joint-powers authority in Southern California includes five major water resources agencies, three counties, and several cities located within the same watershed and along the same aquifer, spread geographically from Orange County to the Inland Empire. SAWPA undertakes collaborative planning and implementation activities with multiple agencies and organizations throughout the region. One of these joint efforts brings together city/county planners and watershed stakeholders, an important first step toward developing a system-wide, integrated approach to ensuring that our remaining groundwater recharge areas are not paved over.

Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority: This Northern California agency has completed a first-ever economic valuation of the open space in their jurisdiction. Approximately 60% of the landscape that once recharged groundwater in Santa Clara County is now paved over, according to Healthy Lands and Healthy Economies, Nature’s Value Santa Clara County. The Open Space Authority mapped the location of the remaining 40%, a critical first step in avoiding any further losses.

The authority secured maps of the groundwater basin boundaries from the Santa Clara Valley Water District. Researchers overlaid groundwater basin maps with data from the California Department of Conservation’s Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program to identify recharge areas already lost to development. This exercise enabled the Authority to identify recharge areas that have already been developed and to pinpoint the remaining recharge zones that need to be preserved.

Multi-Benefits of Groundwater Protection

Protecting groundwater recharge zones generates other rewards, too. Besides replenishing our groundwater supplies, these measures can also assist flood control, reduce water pollution, enhance habitat, and improve public health.

Flood Control: In Fresno, the Metropolitan Flood Control District collects stormwater in basins that act as both flood-control mechanisms and aquifer recharge areas, replenishing the county’s primary source of drinking water. Several basin areas also double as recreational sites.

Reducing Water Pollution: Urban runoff is the largest source of water pollution. As rain and outdoor irrigation water flow over lawns, streets and parking lots, it gathers up contaminants and deposits them into our water bodies. More compact development is an important strategy for accommodating growing populations while preserving groundwater recharge areas. California’s land-use legislation (AB 859) encourages compact development and the preservation of undeveloped open space. And U.S. EPA water experts conclude that higher-density scenarios reduce the amount of urban runoff per house and per lot, thus potentially reducing pollution.

Moving Forward

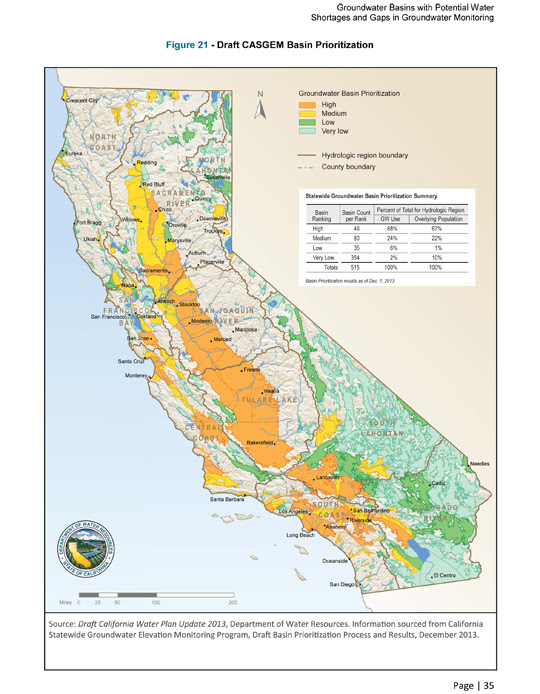

Continual (albeit limited) attention has been given to groundwater recharge since 2009, by both the California Department of Water Resources and the Legislature. California’s four-year drought, however, has brought this issue into sharper focus.

In September 2014, Governor Brown signed into law the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act – historic legislation requiring for the first time comprehensive and sustainable management of California’s critical groundwater resources. The Act requires the formation of new “Groundwater Sustainability Agencies,” or GSAs, which will be charged with preparing “Groundwater Sustainability Plans” (GSPs) to assure that our precious groundwater supplies are sustainable for the long term. Achieving sustainability will require these new, regional agencies to balance their water budgets; ensuring that “withdrawals” do not exceed “deposits.” Thus, groundwater recharge will be front and center.

Groundwater Sustainability Agencies are to be formed around shared water basins, not socio-political boundaries. As most groundwater basins are shared by multiple overlying jurisdictions and the GSPs will impact all of them, it is imperative that each jurisdiction participates in the process. Ideally, all jurisdictions sharing the same aquifer – cities, counties, water agencies, tribes and special districts – will work together and jointly produce their Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP). The unique partnership established by the Santa Ana Water Project Authority may serve as useful model for other jurisdictions to follow.

The Department of Water Resources is currently defining California’s groundwater basin boundaries (draft released July 20) and developing guidelines for Groundwater Sustainability Plans. Local governments and stakeholders sharing the same groundwater basin have until June 30, 2017, to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies.

The GSAs responsible for critically over-drafted basins (as identified by DWR) must complete their Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP) and submit it to the Department of Water Resources by January 31, 2020. All other GSAs have until January 31, 2022, to submit their Plans.

Local Governments Should Start Planning Today

While many have applauded the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, there is also concern over the protracted deadline. Vast acreage of land could be paved over and aquifers over-drafted before Groundwater Sustainability Agencies complete their plans and attain sustainability-GSAs have until 2040-42 to balance their groundwater budget.

Local governments can take action to mitigate this immediate threat. Celeste Cantu, former executive director of the State Water Resources Control Board and now General Manager of the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority, recommends that cities and counties establish a “W” zone (for Water) around every important aquifer recharge area (similar to an “A” designation to restrict land for agricultural uses) in their jurisdiction to control development of this precious ground.

To be eligible for infrastructure grants from the Department of Water Resources, AB 359 requires that water agencies provide local planning agencies with a map of important recharge areas.

Thus, available information is sufficient for local governments to locate functioning aquifers, using the technique pioneered by the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority. By overlaying water agency maps with maps from the California Department of Conservation’s Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program, local governments can identify the aquifers within their jurisdiction that are still functioning and then take actions to protect them from development.

If local governments identify and save our natural recharge areas today, it will reduce economic pain and save money in the future. Otherwise, if the drought continues and when another drought arises, we will have to resort to more drastic anti-drought spending and more austere conservation measures. Adapting an old proverb, an acre saved is a gallon earned.

Resources

The Ahwahnee Water Principles: A Blueprint for Regional Sustainability

Thanks to contributing author Judy Corbett.