October 30, 2020

Topic

California is simultaneously in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and the second-worst megadrought in the past 1,200 years.[1]

This convergence is exacerbating the drought-fire-flood cycle: Drying of vegetation from drought creates more fuel for fires. Fire then leads to erosion of lands that would otherwise handle stormwater during flood events. After the fire, stormwater runoff then pollutes and drastically impairs water supplies. In a post-fire landscape, vegetation crucial for groundwater recharge can take as long as five years to regrow.

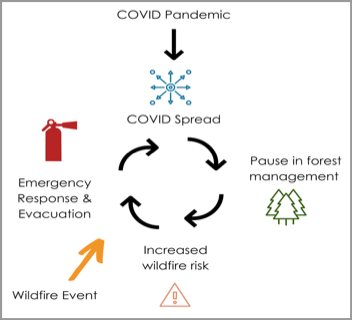

These wildfire effects on California’s watersheds[2] also have devastating community and economic consequences. Furthermore, a pause during the pandemic on forest-management approaches, which would otherwise curb wildfire disaster, increases our vulnerability and leaves many Californians in a heightened state of anxiety.

The devastating toll of California wildfires

The numbers don’t tell the whole story, but they are a good place to start. This year, we’ve already seen 4.2 million acres burned, with more than 9,300 buildings destroyed and 31 fatalities with 14 major fires/complexes still burning, including the August Complex – now the largest recorded fire in state history with more than one-million acres burned. This follows two years of some of the state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfires. Five of the top 10 largest fires in California history have struck this year. In 2017-18, wildfires killed 147 people, burned 3.5 million acres and destroyed more than 34,000 structures.

With over 4.5 million homes and 11 million people living or working in the wildland-urban interface, combating this danger is crucial to California’s future.

In addition to the damage to lives, land and buildings, wildfires expose watershed regions – crucial to the state’s water supply and our rural communities – to increased risk. The topography of California’s headwater regions makes them especially susceptible to erosion after wildfires.

COVID impacts on watershed management

In California state forests, controlled burns are an effective approach to wildfire mitigation, but were called off due to COVID-19 in an effort to decrease smoke exposure to communities and decrease spread of virus among firefighters. These forests contain more than one-half of the Sierra headwaters, the state’s primary source of water.[3]

While the pandemic has temporarily led to overall reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, these gains may be rendered negligible by the increased risk of wildfire devastation. In 2018, wildfire released nine times the greenhouse gas emissions (45 million metric tons of CO₂) than were reduced by the state.[4]

According to Governor Newsom, the pandemic has placed California in a $54 billion deficit. Unemployment rates shot up from 3.8% in February to 11% in September. The Governor’s Budget includes $85.6 million in Cal Fire’s fire protection and capacity, and new investments in wildfire prevention and mitigation.[5] There is $117.6 million for the Office of Emergency services for emergency preparedness and response including enhanced wildfire forecasting.[6]

Policy implications and opportunities

Emergency response during the pandemic: The state is currently pursuing changes to overall emergency preparedness and best practices.[7] Where evacuation is necessary, there is more focus on providing clear air spaces and shelters that are accommodating for COVID-19 measures. COVID affects the ability and willingness of fire crews to bring on additional workforce, which requires further health and safety measures, and increases everyone’s risk of potential exposure to the virus.[8] Firefighters are encouraged to take extra precautions by physically distancing, holding briefings remotely, and following strategic scheduling methods to minimize risk of spread.[9]

Managing our forests: State efforts should focus attention to high-priority forest health projects that sequester carbon and reduce wildfire risk. Thinning at least 1 million acres of forested land annually for 10 years is critical to managing wildfire disasters.[10] Forest management and thinning will reduce fire risk and GHG emissions, and also protect water quality by mitigating sediment and debris, and reduce the cost of future wildfire response. Increased investment in forest management and restoration will directly enhance California’s water supply availability and reliability;[11] the state relies on the fire-prone Southern Cascade/Sierra Nevada region for more than 60% of its water supply.[12]

Jobs where they’re most needed: Forest management and wildfire-response training opens the door for job programs and pathways, especially essential in rural mountain counties, which suffer higher levels of un- and under- employment – which also happen to be the same communities most at risk to wildfire.[13] When the unemployment rate is especially high (such as now, as a result of COVID), local economies previously dependent on tourism and hospitality must pivot. This is an excellent opportunity for regional investment in upper watershed communities for forestry and wildfire workforce development programs that will directly benefit downstream users.