June 30, 2015

Topic

“Getting people to use less water and use it more wisely is our #1 goal.”

– Felicia Marcus, Chair, State Water Resources Control Board

With statewide mandatory cutbacks, cities are taking drastic steps to reduce their water use. But some efforts – like cutting all outdoor water use unilaterally – have dire consequences. For example, encouraging residents to purposely let lawns die can inadvertently kill our trees. Squandering our community’s investment by letting our urban trees die will have immediate and lasting consequences. As we make important decisions about where to cut water use, we must consider these long-term consequences.

Fortunately, it’s easy to save water AND keep trees alive.

Drought and California Landscapes

By now, everyone knows we’re in a severe drought. Even the federal government is stepping in to help “drought-stricken California.” The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation announced another $6.5 million in grants last week for water efficiency in our state.

“The entire government is dedicated to helping respond to continued drought conditions. We know that water is the lifeblood of our communities and every drop counts,” U.S. Interior Secretary Mike Connor said.

In April, Governor Brown strengthened his resolution on the drought with Executive Order B-29-15, calling for a 25% statewide reduction in urban water use with designated local targets.

Much of the urban water-use reduction efforts have focused on outdoor landscaping. The typical California landscape is similar to the rest of the country: large swaths of green grass, with a few shrubs, trees and flowering plants as accent pieces. Keeping those lawns green in our arid climate requires a lot of water. According to the Department of Water Resources (DWR) and other sources, outdoor landscaping accounts for about 50% of all urban water use.

A few communities such as Roseville, San Jose, Monterey County, Irvine and San Diego are leading the way with recycled water for outdoor irrigation, but the vast majority of California’s communities still use potable water for their outdoor landscapes.

Efforts to change social expectations and gain acceptance of a more California climate-appropriate landscape have long been underway. Local agencies have been required by the state to adopt a water-efficient landscape ordinance (WELO) since 1993, but enforcement of these ordinances has been minimal. Recent drought restrictions and the 2015 update to DWR’s Model WELO are helping these changes to finally take root.

CivicWell’s February 2015 Livable Places Update featured a number of municipalities that are leading the way on recent drought-resilient landscape ordinance upgrades.To save our water and our trees, it will take all of us working together – state agencies, local governments, residents and community groups – to ensure immediate drought relief and long-term drought resilience.

The State Water Board’s emergency drought regulations prohibit watering street-median turf with potable water, but still allow trees and shrubs to be watered. However, many communities are shutting off municipal irrigation all together – forgetting the needs of their trees.

California communities have made a long-term commitment to urban greening, recognizing the many benefits urban forests provide. CivicWell is working with an ad-hoc consortium of state agency and community group representatives on a campaign to help California “Save Our Water and Our Trees.”

Trees Are Worth the Water

California’s severe drought is forcing us to make difficult decisions about where limited water should be used. Communities have invested in trees, because they’re important.

Watering trees to keep them alive during drought doesn’t waste water; it is a prudent use of our limited resources to preserve an important community investment. Sometimes an overlooked feature in our urban and suburban landscapes, trees provide multiple benefits for the economy, the environment, public health and general well-being.

Urban trees require little water and minimal care, but they provide a significant return on investment.

The City of Clovis’ Urban Forest Management Plan concluded that every $1 spent on public trees resulted in $2.40 in public benefits.

Anyone can estimate the annual benefits provided by an individual street-side tree, using only the location, species and tree size.

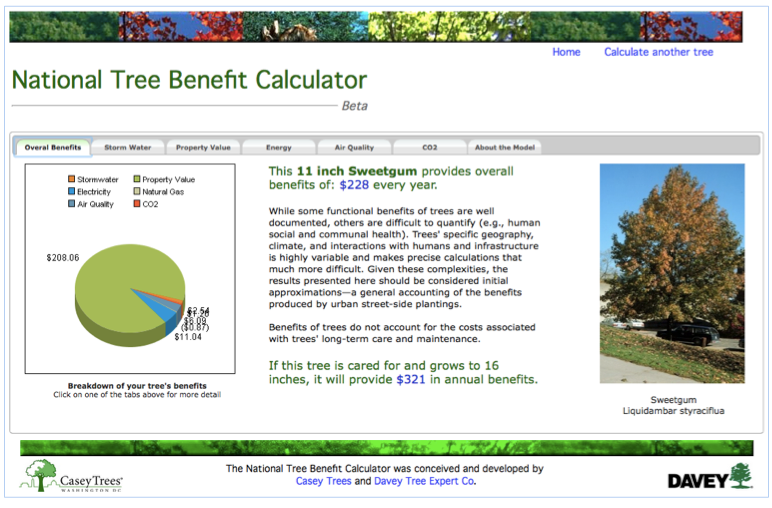

The National Tree Benefit Calculator

The National Tree Benefit Calculator is a simple and accessible online tool to help communities understand the value of trees. Benefits are calculated for both economic and environmental parameters such as stormwater, property value, energy, air quality and carbon dioxide levels, and are summarized in a total dollar value. For example, an average sweetgum tree in a Sacramento neighborhood generates $228 of annual benefits to the community and:

- Captures over 300 gallons of stormwater runoff.

- Increases property value by over $200.

- Conserves 95 kilowatt hours of electricity.

- Reduces 168 pounds of carbon in the atmosphere.

- Improves air quality by intercepting dust, absorbing pollutants, cooling temperatures, and releasing oxygen.

Check out the tree benefits calculator here.

Economic Benefits of Trees

In a number of ways, money really does grow on trees.

Trees stimulate downtown business. Consumers shop more often and longer in downtown areas with street trees, will pay more for parking, and are willing to pay up to 11% more for goods and services in well-shaded shopping areas.

Trees increase residential property values. Homeowners are willing to pay 3-7% more for properties with ample tree shade versus those with few or no trees. Each large front-yard tree adds about 1% to a home’s resale value.

Trees generate local jobs. The City of Bakersfield has over one million trees growing within 408 square miles, providing an average tree canopy of 10%. Caring for these trees is a $20 million industry, providing 750 local jobs.

Environmental Benefits of Trees

Trees improve our climate and save energy. Neighborhoods with well-shaded streets can be up to 10° F cooler than neighborhoods without street trees. According to the Journal of Arboriculture, residential trees can lower energy demand from air conditioning bills by up to 30%, while reducing winter heating by 25%.

Trees clean our air. Trees store carbon dioxide, absorb harmful acid rain-producing pollutants, and intercept dusty particles, while releasing clean oxygen into the air through photosynthesis. Just 100 trees are needed to remove five tons of carbon dioxide and 1,000 pounds of pollutants from the air each year, including 300 pounds of particulates.

Trees improve our water management. Tree roots hold soil in place, enabling water storage, filtration, pollutant removal, groundwater recharge, and stormwater flow reductions. The City of Los Angeles has roughly 350,000 trees in city parks. These trees capture more than 360 million gallons of stormwater every year. More info here.

For more on the water benefits of soil, see “Soil as a Sponge” in the January 2015 Livable Places Update.

Public Safety Benefits of Trees

Trees calm traffic and encourage walking. Street trees encourage safe speeds and quieter neighborhoods by providing visual interest and a way for drivers to gauge their speed. Trees planted between the curb and sidewalk improve safety by adding a buffer between moving vehicles and pedestrians.

Trees reduce crime and increase social ties. Green spaces draw people outdoors, increasing surveillance and discouraging illegal activity. A study from the University of Illinois Human – Environment Research Lab observed 52% fewer property and violent crimes at apartment buildings with greenery than at those with little or no vegetation. They concluded that a property’s green and groomed appearance is a signal that residents care about the property and watch over one another.

Killing Trees Is Costly

Trees need very little water to stay alive, in contrast with thirsty ornamental turf and other plants. Communities have already invested millions in their urban tree canopy, recognizing the innumerable public health, economic, and quality of life benefits trees provide. Preserving this investment is a necessary and beneficial use of our limited water resources.

The most immediate impacts of letting our urban trees die are the financial liability and the public health/safety risk posed by dead trees. Falling trees cause significant property damage and pose a significant risk of injury.

Dead trees are also far more susceptible to fire. Removing these dead, dangerous trees costs anywhere from $1,400-$2,600 each. Long-term economic impacts include lower property value, reduced commercial activity, and increased costs from environmental mitigation (due to reduced air and water quality) and public health (from extreme heat and air quality). Not to mention the lost ancillary urban habitat and quality-of-life benefits.

The City of Los Angeles’ abundant park trees would cost over $2 billion to replace. The LA Department of Recreation and Parks estimates that as many as 14,000 park trees – about 4% of the total – may have died during the last year of drought. (Los Angeles Times, June 12, 2015.)

The death of so many trees may drive up temperatures, wreak havoc on habitats, and limit the capture of water. Temperature increases from tree loss will increase municipal water demand, smog levels, and human discomfort and disease.

Local Action: The Right Moves and the Wrong Ones

If we want to preserve vibrant, livable communities that are climate- and drought-resilient, some local drought response actions need be reevaluated.

For example, one county has stopped caring for all of their stressed redwood trees because they cannot stay on top of the watering needs.

One Bay Area city is still watering their street medians twice a week, but are not watering long enough to reach the trees’ roots, inadvertently wasting water. Read more here.

Another Bay Area city is requiring property owners to care for public street trees.

Our city and county leaders need to set a positive example for their residents, cutting back water use yet properly caring for their trees. Here are some good examples:

The City of Thousand Oaks invested in biochar – a highly efficient charcoal made from biological material – as a carbon-friendly soil improvement. The biochar worked far better than expected, removing the need for synthetic fertilizers and cutting water use by 50%.

Biochar acts like a sponge. Once activated by natural fertilizer or compost, it retains moisture and releases nutrients for healthy plant and tree roots.

Thousand Oaks has applied 31 cubic yards of biochar to date, sequestering over 90,000 pounds of carbon within its soil. Applying biochar to the area around trees will improve overall tree health and retain water in the soil longer.

The City of La Cañada Flintridge is using general funds to buy recycled water from nearby Glendale to save their trees during drought. La Cañada doesn’t have its own recycled water project, but Glendale has a program designed for construction projects to purchase recycled water from the city’s hydrants using removable meters. The meter tracks water usage, and the city bills the user accordingly.

La Cañada is close enough nearby that they can purchase water from Glendale’s meters at about $24 per watering and truck it to their street trees at a reasonable cost.

Save Our Water AND Our Trees!

Municipalities can set an example for their residents by demonstrating proper tree care and water-efficient landscape irrigation. Here are a few steps your community can take right away:

- Redirect funds saved from reduced watering to retrofit your irrigation system for trees.

- Replace sprinkler systems with drip or soaker hoses.

- If you have to turn off your irrigation system, use watering trucks or mobile irrigation units to keep your community trees alive.

- Use recycled non-potable water for landscape irrigation.

- Add proper tree care to municipal landscape, tree, and/or irrigation ordinances.

- Educate your agency, and then educate your community.

Continue to invest in urban greening

CivicSpark, in partnership with CivicWell and the Urban Forests Council, will be providing technical assistance for the Cal Fire Urban and Community Forestry Program grant applications. Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund Grants are part of the State’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategy. Awards can range from $500,000-$1.5 million for projects that help disadvantaged communities implement tree programs.

Statewide leadership is asking communities not to plant new trees now, but to prepare for planting in the cooler fall/ winter months. In addition to tree planting, these grants can be used for Tree Inventories and Management Plans, Biomass Utilization, Parcel Purchase and Greening and Innovative Green Infrastructure Projects. For more information contact Elizabeth Lanham, Program Manager for Urban and Community Forestry Technical Support, California Urban Forests Council at projectmanager@caufc.com or check out this online resource.

Learn to properly care for your trees, and how to recognize when something’s wrong

Resources abound to assist communities in properly caring for their trees, even in a drought.

CivicWell and the Center for Urban Forest Research and Education developed tree selection and planting guidelines for the San Joaquin Valley, Southern Coastal California and the Inland Empire. See these guidebooks and more resources about trees and urban planning.

CivicWell has compiled a list of our other favorite resources: