April 27, 2018

Topic

“Curbside management is a hyper-local challenge. Any strategies for managing curb space are going to be most effective when they are made on essentially a block-by-block basis and based solidly on information or data pertaining to the needs of the area and current curb usage.”

Leona Agouridis

Executive Director, Golden Triangle Business Improvement District (Washington, DC)

City curbs and sidewalks are becoming increasingly crowded as ride-hail companies and delivery businesses like Amazon Prime vie for pick-up and drop-off real estate, and bikeshare programs and dockless scooters flood communities across the nation. The spaces at the edge of our streets have evolved so rapidly with the arrival of new mobility and increased delivery needs that local land-use planners and regulators are struggling to create policies that keep pace.

Advancing technology innovation, growing frustration with congestion, and increasing environmental regulation have converged to create a demand for a wider range of services with new approaches to meeting people’s mobility needs. These new services are coming fast and furious:

- Rise of ride-hail/transportation network companies: Uber alone now provides 5.5 million rides per day globally, while Lyft (its closest competitor in the U.S.) reached the one million daily rides mark last July. In San Francisco, transportation-network companies account for about 20 percent of traffic – and 65 percent of traffic violations.

- Growing influence of e-commerce: Last year, Amazon shipped more than 5 billion items worldwide through its Amazon Prime program. The growth rate of e-commerce is estimated to be 20% annually in many cities, according to Michael Browne, a logistics and urban freight transport professor at the University of Gothenburg’s School of Economics, Business and Law (Sweden). Parcel volume increased by nearly 50 percent from 2014 to 2016 and will only continue to grow along with the trucks delivering the packages.

- Surge in electric scooters: Shared, electric, dockless scooters, which emerged in Santa Monica in September 2017, are now on the sidewalks of San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Washington, DC, and Austin – and looking to expand.

- Booming bike-share: Bike-share is growing in communities across the U.S., with more than 88 million trips made on a bike-share bike in the U.S. since 2010, according to the National

Association of City Transportation Officials. In 2016, riders took more than 28 million trips, on par with the annual ridership of the entire Amtrak system.

These changes have made an often-overlooked part of city infrastructure – curbside space – fertile ground for social and mobility disruption. Delivery trucks, electric-vehicle charging stations, bike lanes and racks, parking spaces and ride-share services all play into the dynamics of the curbside ecosystem now.

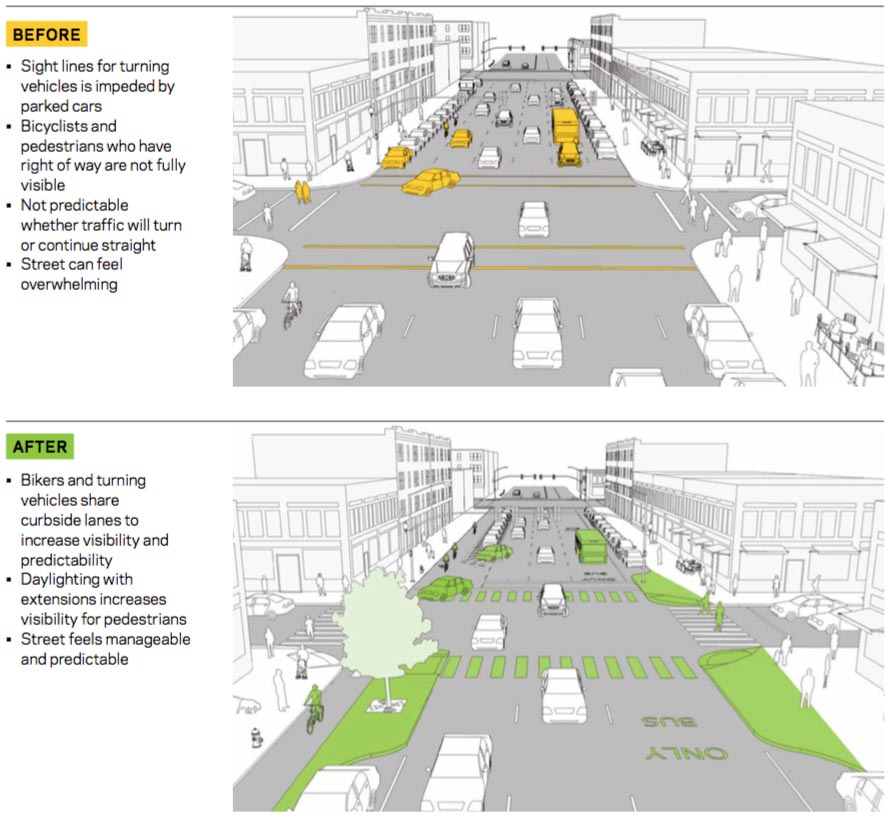

Listen to the data: Increase space available for bikes, scooters, pick-up and drop-offs

Communities with constrained space who are seeing increases in deliveries, pick-up and drop-offs and bicycle, pedestrian or other micro-mobility use (e.g. electric scooters, segways, unicycles) may need to consider removing parking spaces for cars (not always a politically popular decision) to accommodate other transportation modes that may be more in line with the community’s environmental, health and safety goals. Eliminating a parking spot per block in a congested area could allow for bike parking, personal electric transport (PETs), parklets or designated pick-up/drop-off areas.

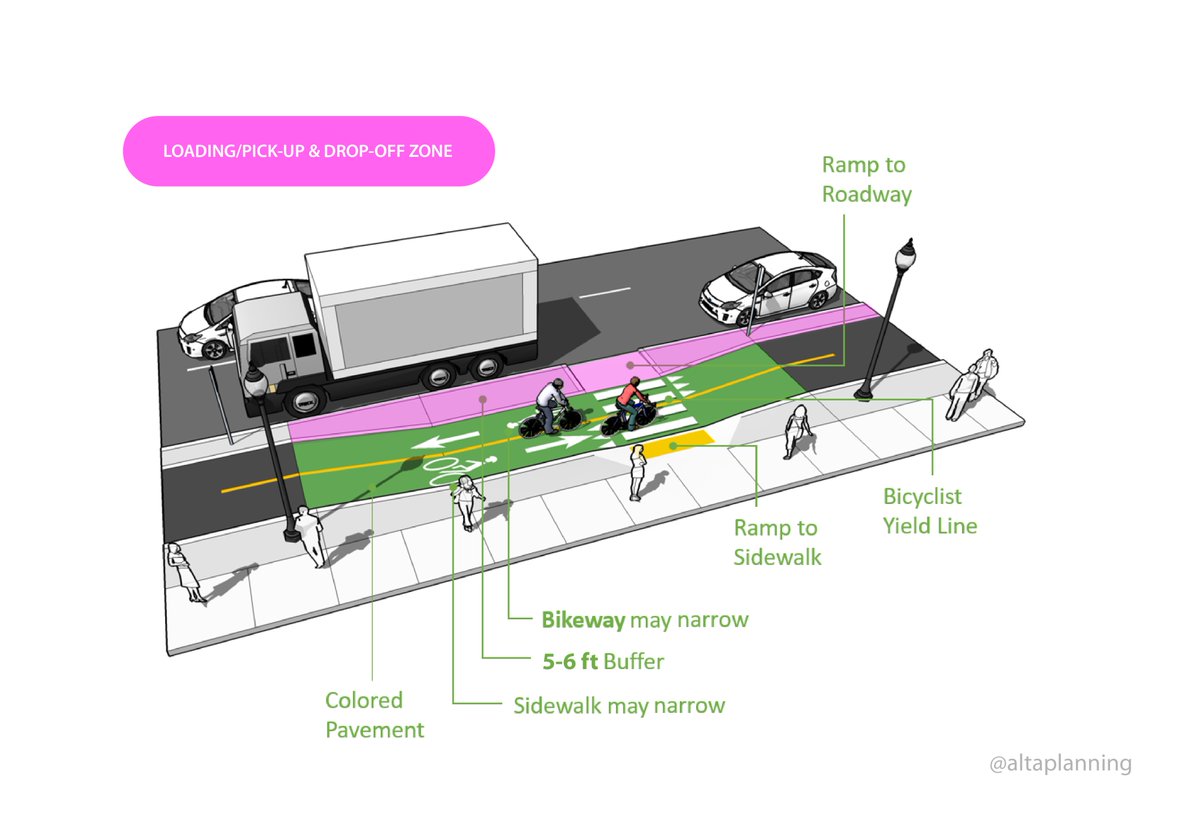

Designate Shared Use Mobility (SUM) zones

Cities could choose to designate a select number of curb spaces at the beginning or end of each block in heavily trafficked areas as Shared Use Mobility (SUM) Zones. In these zones, transportation-network companies and taxi drivers could safely conduct passenger pick-ups and drop-offs during peak hours, allowing these drivers to exit the traffic lane (avoiding blocking other drivers) and pull over to the curb so their passengers have safe passage to the sidewalk.

Outside of peak hours, these spaces could be converted back to regular parking spaces for consumer vehicles or, where needed, be designated as commercial delivery zones to prevent congestion caused by double-parked trucks. Uber and Lyft are working with cities like Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, CA to establish such designated zones.

Charge fees to cover additional municipal costs

Some cities and many airports charge transportation-network companies a fee for pick-ups and drop-offs conducted in their jurisdiction. Cities could charge a nominal fee, perhaps $0.25 or $0.50 per pick-up in a geofenced area where there are active Shared Use Mobility zones to recover any lost revenue that would otherwise be generated by hourly meter parking.

Fees for electric bikes and scooters could fund the public-sector staff time dedicated to coordinating and overseeing dockless companies. Bird, a purveyor of shared electric scooters, pledged to donate $1 per vehicle per day to each city to promote bike-lane infrastructure and safe riding.

Set limits on dockless bikes and scooters

Many major U.S. cities have rules that limit how many dockless bike and scooter companies can operate, and how many bikes or scooters they can offer as a way to avoid problems with blocked sidewalks.

Reassess speed to account for evolving mobility services and needs

Reducing car speed limits in dense urban areas to 20 mph could reduce the risks that might be associated with increases in personal electric transport, bicycling, deliveries and pick-up/drop-offs.Any measure taken should seek to balance environmental goals along with local capacity to respond to and meet the travel needs of all community members who have a stake in the availability of these public spaces and mobility options.

What cities are doing

Washington, DC’s Department of Transportation partnered with the Golden Triangle Business Improvement District to devise solutions in a portion of Dupont Circle that experiences heavy vehicle and pedestrian traffic. During the pilot period, daytime curbside parking spaces are converted to ride-share pick-up/drop-off zones on weekend nights. The program aims to boost safety and reduce traffic tie-ups from vehicles stopping in travel lanes.

Fort Lauderdale implemented designated ride-share zones as part of its six-month plan to boost safety – through its Vision Zeroprogram – and mobility along the popular commercial stretch of Las Olas Boulevard. The plan includes new daytime-delivery loading zones to discourage double parking and unloading in travel lanes. Some of those zones transition to parking spaces from 5:00 p.m.-3:00 a.m. The City also added new bike lanes – many of which are protected – that UPS delivery employees have been using as part of the e-trike pilot program.

San Francisco’s Mobility Committee is considering an ordinance to address growing concerns around dockless electric scooters that would beef up local laws about blocking sidewalks and streets, and commercial use of City right of way. If adopted, the ordinance would prevent businesses from allowing their scooters to park on a street, alley or sidewalk.

Austin is considering an ordinance that would give the City’s transportation director authority to bar a person or business from operating on city rights of way if the operations are determined to be detrimental to safety and mobility.

“The city code is outdated and does not specifically cite dockless mobility options … pertaining to right of way use,” Transportation Director Robert Spillar told the Austin City Council. “In order to forestall a predictable and unmanageable swamping of our streets with thousands of vehicles, (the department) recommends a more nimble response…”

Spillar recommends granting six-month permits to dockless companies, beginning May 1, with a $30 fee per bike or scooter and a limit of 500 bikes or scooters for each licensed company. Under the proposal, violations would be a Class C misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of as much as $500.

Where we go from here

Emerging mobility solutions could help cities reduce greenhouse gas emissions, address vexing first-mile/last-mile gaps and reduce the need for car use for short trips. The potential is already there: Half of all trips are three miles or less but 72% of them are made by car.

Nonetheless, local governments are increasingly at a disadvantage to keep pace with rapidly evolving mobility changes (and the companies pushing their implementation) that affect community infrastructure and mobility needs.

Outdated codes, models and policies are often not sufficiently nimble and flexible to anticipate these market disruptions. That makes it all the more critical for local governments to use the leverage they do have to secure and optimize community benefits from these new enterprises.

How cities use their curb space will send important signals to private-sector providers and the public which modes are encouraged and prioritized – and how we can best balance and share the edges of our streets.