January 26, 2022

Water is more than a commodity; it is a building block of life and fundamental to the health and livelihood of all Californians as well as the ecosystems we rely on. These recommendations promote cooperation and flexibility between water providers and customers in order to meet community needs and stabilize long-term revenue streams.

Download PDF: Water Accessibility and COVID Lessons for Resilience

PANDEMIC RECOVERY AND BEYOND

Water Accessibility and COVID Lessons for Resilience

Shutoff moratorium: Helping customers keep the water on after the pandemic

In recent decades, a dire combination of environmental, economic and social crises have rocked California – drought, fire and flood, insufficient affordable housing, inequality and racial unrest, a global health pandemic and the economic instability that followed. Added to these is another looming crisis that may restrict access to water for millions of California households, many who have never faced shutoffs before.

This crisis does not stem from water scarcity, but instead from overdue water bills that customers struggle to pay.

The pandemic exacerbated many already existing problems about inequities in education, housing and income. The difficulty for water providers to cover costs associated with delivering water to customers in the effort to preserve public health during the pandemic demonstrates how California’s water delivery system is “fiscally brittle.” This means that many water agencies have difficulty generating enough revenue to cover their operating expenses during economic downturns. That’s also a problem when drought restrictions are in place, as is expected later this year.

Furthermore, the pandemic has exacerbated financial problems for small water systems long before the pandemic.

To understand how and why our water-delivery system is brittle, we must first understand how water is paid for and provided in California. Water is defined as a “public good,”so households only pay for water treatment and delivery.

Even under the best circumstances, water agencies – especially the smaller ones who purchase water from other agencies – have a thin profit margin. As a result, it is a monumental task for the average water provider to build up large financial reserves, especially as costs increase due to aging infrastructure and climate-change impacts. This leaves water providers unprepared when customers en masse can’t pay for their water service.

This situation is further complicated by the producer-consumer relationship established between water agencies and ratepayer households. Water agencies rely on water-delivery fees collected from households, based on the amount of water they use.

Water Obstacles

Regulatory Restrictions

Over the years, several state propositions (Propositions 13, 218 and 26) have made it difficult to adjust water rates to changing circumstances. Prop 13 classified water bills as a tax, imposing the two-thirds majority vote requirement to change fees, while Prop 218’s proportionality clause made it illegal for agencies to apply revenue collected from one customer to cover the cost of service to another customer.

Prop 218 and Prop 26 both restrict how water agencies set their water rates. During periods of economic downturn, this rigid system harms everyone – establishing a cycle in which households become unable to pay for their water service, which results in the agency being unable to cover their cost of providing that service. If water agencies can find a way to raise rates to recover their lost revenue, their service becomes even less affordable to struggling households, leading to greater inequities, more unpaid bills and continued lost revenue.

Shutting Off Water Service During the Pandemic

During the pandemic, high unemployment and reduced incomes made it difficult for many families to afford the essentials, including their water bills. One tool used by water agencies to encourage payment of overdue bills is shutting off a customer’s water. Agencies use this tactic to get the ratepayer revenue that covers their operational costs.

This presents a problem for both the agency and their customers when households are simply unable to pay their water bills. Not only is safe, clean drinking water and sanitation a basic human right, but shutting off someone’s water also poses a unique public health-and-safety risk during a pandemic. Water is essential to maintaining hygiene and housing stability.

When the health risk posed by water shutoffs became clear, Governor Newsom intervened. Executive Order N-42-20 (April 2020) prohibited all public and private water providers from shutting off service to residences during the pandemic. In tandem, the California Public Utilities Commission issued Resolution M-4842, which requires private water utilities to implement reasonable payment options for customers, in an effort to ensure that water providers work cooperatively with customers to resolve unpaid bills and minimize shutoffs.

Water Shutoff Moratorium Results: Saving Lives and Money

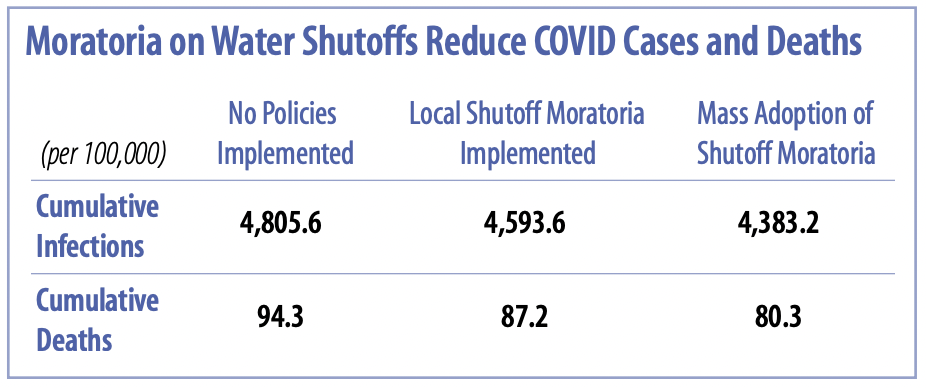

The moratorium on water shutoffs sought to protect the health and well-being of California families – and it worked. Shutoff moratoriums across the country (including California) decreased COVID infections by 4.4% (585,200 people – more than the combined population of Long Beach and East LA) and COVID related deaths by 7.4% (20,952 – about the crowd capacity of a pro basketball arena) over nine months, according to a Duke University study published in January 2021.

If a national moratorium had been implemented during the same time frame, the outcome could have doubled to 8.7% fewer COVID infections and 14.8% fewer deaths – roughly 1.15 million (about the equivalent of San José) and 41,184 individuals (comparable to the capacity of a pro baseball stadium), respectively.

The reduction in infections is attributed to the water-shutoff moratorium, ensuring that households had access to a reliable source of water to maintain clean hygiene practices during stay-at-home orders – both crucial factors in preventing the spread of COVID and other diseases.

Economic Impacts of Water Shutoff Moratorium

The social impacts and costs avoided by public health departments thanks to fewer infections and deaths were not calculated in the analysis. However, an October 2020 Harvard University study estimated the economic cost associated with the pandemic at $16.1 trillion. They estimated the financial cost of premature death from COVID at $4.4 trillion, long-term health effects at $2.6 trillion, and mental-health impairment such as depression and anxiety as high as $1.6 trillion in lost productivity.

Fewer infections and deaths also mean communities can begin economic recovery from the pandemic even faster.

Impacts on Water Agencies

Despite these gains, the moratorium exacerbated an already existing problem among many water agencies – how to secure sufficient revenue to maintain existing water infrastructure and support projects that improve service reliability.

A major component of agency budgets is the projected revenue from utility fees – how much water their customers use and pay for. The unemployment crisis during the pandemic has dealt an unexpected blow to that revenue stream when it left many households unable to pay their water bills.

While the water-shutoff moratorium helped ease the immediate financial burden on households and produced tangible health benefits, it is certainly not a long-term solution. The moratorium didn’t absolve customers of debt accrued over the past year-and-a-half, nor did it provide water agencies with the financial means to continue operating over the long term. It merely ensured households would continue receiving water while the fees owed to their water agency compounded.

A January 2021 analysis of debtors by the California State Water Resources Control Board found that there is an estimated $1 billion in unpaid water bills statewide. This makes the $400 million in statewide rental debt quite small by comparison.

The water debt is estimated to be held across 1.6 million households – at least 12% of California families. Although the average debt is roughly $500 per household, the distribution of Delinquent Accounts places the majority of debtors owing less than $300. Lower debts imply that many of these households are likely new debtors as a result of the pandemic.

Water debt has also disproportionately affected disadvantaged communities and smaller water agencies, both of which have less capacity to take on increased debt.

“These small systems have experienced $23.5 million in annual revenue decline since the pandemic began,”according to a Pacific Institute study. “Customers of small systems have accumulated $38.5 million of water-related debt and require assistance.” [Access the full report here.]

Communities that are already economically distressed will likely struggle more during the unemployment crisis. Small water agencies have a smaller ratepayer base: When their customers can’t pay their bills, the agencies must delay capital improvements and/or look to raise rates – which only exacerbate the affordability issue. Small water systems requesting federal or state financial assistance serve 200,000 people in California. Delays in capital projects and rate increases may result in negative impacts to these agencies’ ability to provide safe water to their customers.

Once the moratorium is lifted, water providers may resort back to shutting off services to collect from their customers. The decision to shut off water service would increase the risk of COVID transmission, or force customers to choose between paying a water bill and other necessary expenses, further exacerbating inequalities as the pandemic continues.

Two questions remain: What kind of support is available for struggling households facing water utility debt; and what can water agencies do to mitigate anticipated financial losses?

Government Support to Water Providers to Resolve Debt Crisis

Federal Funding

At the onset of the pandemic, the federal CARES Act allocated $900 million – nearly $50 million for California – to help low-income households pay their utilities. The December 2020 CARES Extension Act also provided $638 million nationwide (with about $60-70 million allocated to California) for water-debt relief.

This type of aid benefits both households and water agencies since it enables customers to pay their bills on time, ensuring that water agencies receive the necessary funds to maintain operations. Yet, these acts vastly underestimate the scale of the problem faced. The amount allocated is not enough – for California or the nation. The combined $110-120 million to California for water-debt relief makes an 11%-12% dent in the $1 billion January estimate. Water debt likely continued to increase since January.

The funding shortfall is exacerbated by the lack of a federal assistance program for water bills. Residential energy bills, unlike water bills, can be partially paid for through the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). The latest pandemic bill, enacted in March 2021, temporarily addresses this need by establishing a temporary water-bill assistance program. Between 2021 and 2025, the federal government will allocate funds on an annual basis to states where customers are struggling to pay their water bills. For now, $500 million has been allocated or expended (the remaining funds will likely be allocated in future rounds). This is a big step in the right direction, but it is unclear how much funding will be available in the future.

Direct funds from the federal government are especially helpful in the water context because they circumvent the state propositions (Prop 13, 218 and 26) that restrict how an agency can apply funds internally.

Federal assistance to water agencies is considered “external funds,”and thus not subject to the restrictions – that lets water agencies support their low-income customers through customer-assistance programs.

State Protections

While federal actions have primarily been focused on financial relief, state actions have been concentrated on preventing water shutoffs.

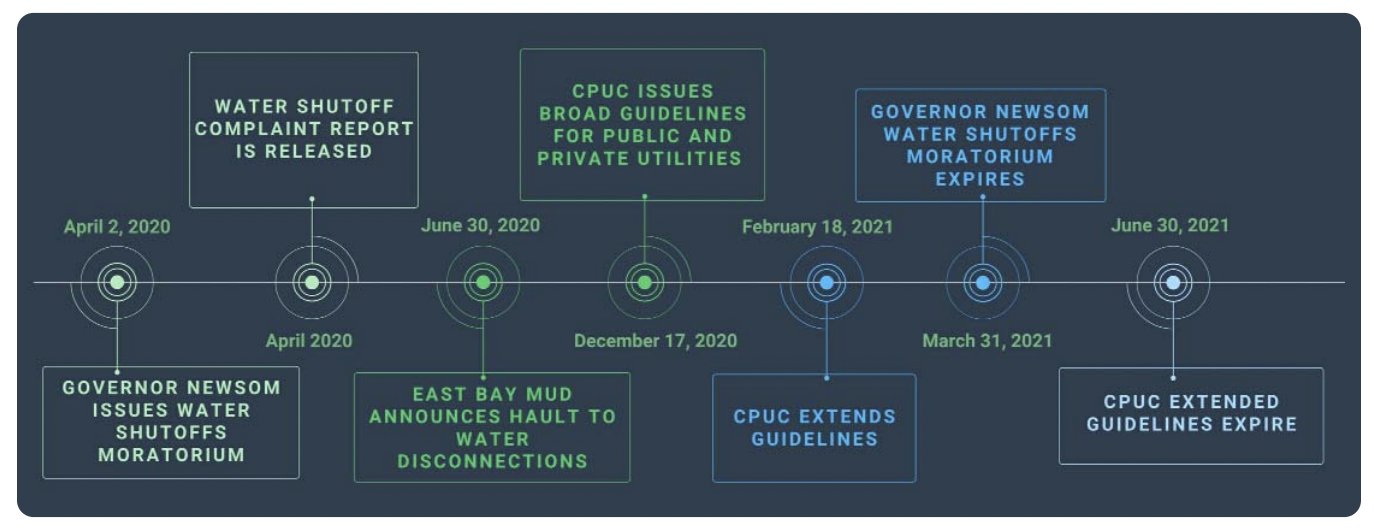

When the Governor’s moratorium on water shutoffs was announced, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) issued broad guidelines on how public and private utilities should respond (timeline below):

Water providers should suspend shutoffs due to non-payment for residential and commercial customers and continue to perform essential functions to ensure clean, safe water delivery. Most importantly, water providers should develop repayment plans to work cooperatively with their ratepayers.

Timeline of State Water Shutoff Actions during the Pandemic

In April 2020, the State Water Resources Control Board launched the “COVID-19 Water Shutoff Complaint Report”to help enforce the moratorium. Individuals can use the State Water Board’s online tool to file an anonymous report on how, when and where a water shutoff incident occurred. (Spanish speakers needing translation assistance can call 844-903-2800 before submitting a shutoff report.) Reports are directed to the State Water Board as well as the water agency that services the specified location for its review. A total of 220 COVID-related water shutoffs were reported since the portal’s launch – more than half of which were received during December 2020.– even with the moratorium in place.

In February 2021, the CPUC extended its guidelines to June 30, 2021; but they only have authority over private water providers, not public water systems. It is unclear what actions will be taken next.

The East Bay Municipal Water District (EBMUD) announced that it will not shut off a customer’s water as long as the COVID state of emergency is in effect, and is currently developing strategies to ensure affordability and continuous access to water services, even after the pandemic. However, the more time passes, agencies’ need to collect past-due utility fees becomes more dire – and water shutoffs more likely.

Legislative Next-Steps

While shutting off someone’s water service may seem unreasonable, this practice is the result of restrictions placed on water providers by state laws and current financing mechanisms. Water providers are almost completely reliant on customer fees to cover the cost of operations. The Legislature considered two bills during the 2020-21 legislative session, SB 222 and SB 223, which would partially address the dilemma created by the shutoff moratorium by changing water agencies’ funding structures.

Senate Bill 222 would create a statewide Water Affordability Assistance Fund to be administered by the State Water Resources Control Board. Before the pandemic, the California Water Boards and the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation justified such an assistance program for low-income households based on the increased retail cost of water, the inability of individual water systems to self-fund a rate-assistance program, and most importantly, the devastating dangers to health and livelihood on people when their water is unaffordable. CivicWell supports passage of SB 222 (which was still being considered by the Legislature at the time of this factsheet’s production).

Senate Bill 223, which died in committee, would have extended and strengthened existing water-shutoff and bill-repayment protections. On the surface, this may seem detrimental to funding sources for water providers, but it is a reasonable compromise.

SB 223 would have also extended existing protections to cover very small water systems (200 or fewer connections) that are currently left out, as well as protected against shutoffs only for those with less than $400 in water debt (excluding late charges and interest) and who are less than 120 days behind on payments. It would have required universal access to extended repayment plans of at least 12 months in duration and also required access to management plans to pay overdue debt.

Both of these bills were sponsored by Clean Water Action, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, and Community Water Center.

Immediate Actions

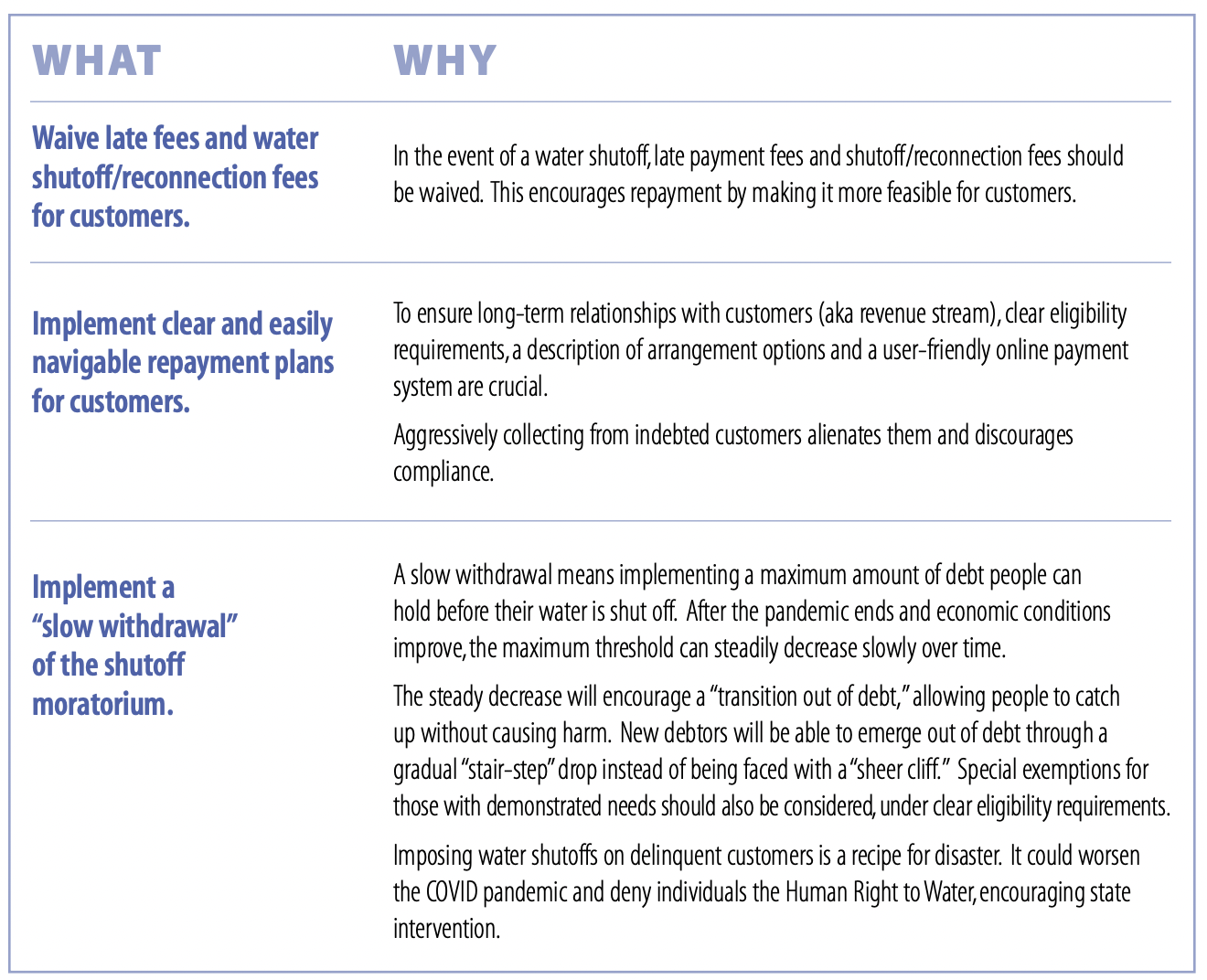

Federal and state actions taken thus far demonstrate that financial relief for customers and/or water agencies is untimely and insufficient. Continued funding injections into a fiscal structure that cannot support itself over the long term is a losing battle. Water providers should consider changing their fiscal management:

- Quickly shifting from pandemic exemptions to normal strict penalties does not reflect the reality or gravity of the pandemic’s long-term effects. Families are struggling and the lingering economic impacts are just beginning to be understood. As a result, a “transition out of debt” approach must be encouraged in the interest of financial stability for water providers.

- The easier it is for customers to pay what they can and when they can, the more likely it is that they will eventually pay their bills.

- Adding more costs to already indebted customers during a time of crisis makes it even less likely that customers can or will pay their bills.

For water agencies to achieve long-term financial stability and ensuring the Human Right to Water, water agencies should pursue the following actions:

Longer-Term Actions

As we look to the future, steps must be taken to ensure water providers are financially strong and resilient to economic shocks.

The State must examine existing data to understand how to best allocate funds and assist water providers.

WHY: The access to a wealth of data has given California an advantage over other states. As a result, informed policy decisions can be made on the ground, based on facts. For example, the State Water Board has identified that small water systems have been impacted the hardest by the pandemic. Therefore, prioritizing financial assistance for them rather than larger water systems makes the most sense.

The State must encourage (voluntary) or enforce (mandatory) equitable, community-driven voluntary consolidation of financially unstable water systems.

WHY: SB 414 authorizes the State Water Board to order consolidation of a public small water system that serves a disadvantaged community if it consistently fails to provide adequate safe drinking water. It directs authority to acquire, control, distribute, store, treat, purify, recycle and recapture any water, and fix a water standby assessment or availability charge.

Advanced Metering Infrastructure can assist households by allowing them to have a greater awareness of their habits and more accurately anticipate costs.

WHY: Households need to be given greater ability to respond to their water use. A way to achieve this is through real-time water-monitoring systems (e.g., Flume, Rachio and Rainbird). These monitors make it convenient for households to track their water use and anticipate monthly costs before receiving their bills. They can also help identify leaks and other anomalies in water usage in real time.

The State should implement a Low-Income Water Rate Assistance Program to help both water providers and households.

WHY: Financial assistance through the federal relief packages has ensured household water bills are paid in a way that maintains revenue to water providers. However, no framework provides continual assistance to families that cannot pay water bills. These financial relief packages are helpful, but are only short-term solutions. Sustainable long-term solutions must incorporate assistance programs for low-income families who cannot pay for their water bills. This approach will provide a future safety net to mitigate water utility debt should another crisis like this occur. Similar programs already exist for energy utility bills on both the state and federal levels.

The State needs to establish a clear mitigation plan in the event of another unemployment crisis.

WHY: One of the issues with the pandemic is the uncertainty surrounding when it will end. This has left decision-makers at the local level unable to anticipate the State’s actions. To provide more clarity on the favored course of action, the State should develop a comprehensive response to mass unemployment.

Funding mechanisms do not allow water agencies to prepare for extended periods of reduced income, even when water is always a priority. Contingency plans that incorporate water rate-assistance programs should be created for water providers.

As we navigate our way out of this crisis, water providers must cooperatively with customers to prevent further financial loss to both parties. These recommendations promote communication and flexibility to help stabilize long-term revenue streams.

Water is more than a commodity; it is a building block of life and fundamental to the health and livelihood of all Californians as well as the ecosystems we rely on. The pandemic has proven how important water is during a health crisis. The inability of water providers to cover operation costs and upgrades during the same crisis presents dire consequences for the future.